Benjamin Harrison Biography

Benjamin Harrison

(1833-1901)

Civil War General, United States Senator, and Twenty-third President of the United States

Great lives never go out; they go on.

– Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison was born in North Bend, Ohio, on August 20, 1833. He received his education at Farmers’ College and Miami University in Oxford Ohio, from where he graduated near the top of his class in 1852. After graduation, he studied law for two years in Cincinnati, Ohio at the office of Storer and Gwynne. Benjamin married his college sweetheart, Caroline Lavinia Scott, in 1853, and they moved to Indianapolis, Indiana a year later. Benjamin opened a law firm in Indianapolis and later joined the law firm of William Wallace (later Civil War general and father of Lew Wallace) in 1855. Shortly after this time, Harrison joined the new Republican Party and campaigned in 1856 for its first presidential nominee, John C. Fremont. In 1857, Harrison entered politics himself and won election as Indianapolis city attorney. He later served as secretary of the Republican State Central Committee and actively campaigned for the 1860 presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln. Harrison later served as the state reporter for the Supreme Court of Indiana, summarizing and supervising the publication of the court’s official opinions.

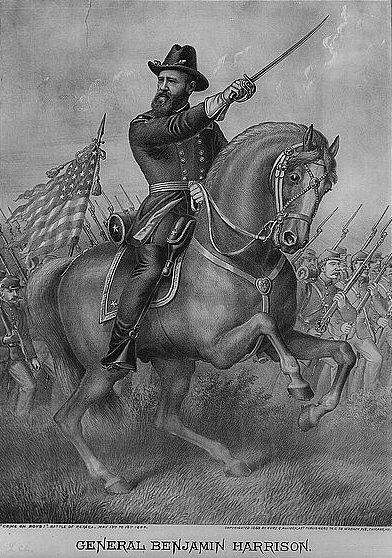

In July 1862, Harrison volunteered to raise a regiment and was immediately commissioned, by Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton, to Lieutenant and was quickly promoted to Captain two weeks later. By August 8, 1862 Harrison had been commissioned Colonel and had raised the 1,000 men that became the 70th Indiana. Harrison, who was named “Little Ben” by his men because of his five-foot, six-inch height, believed in strict, systematic drilling and soon brought his men to excellent fighting form. He saw his first action at Russellville, Kentucky and spent the next fifteen months in Kentucky and Tennessee with his regiment. In 1864, his command was attached to Sherman’s army and fought in the Atlanta campaign. The unit saw its fiercest action in Resaca, Georgia, where Harrison was among the first to storm the Confederate position. After the Battle of Nashville, Harrison was made brevet brigadier-general of volunteers “for ability and manifest energy and gallantry in command of the brigade.”

After the fall of Atlanta, Harrison spent the next several weeks in Indianapolis on special duty by order of Governor Morton. Harrison spent this time campaigning both for himself as Indiana’s Supreme Court Reporter and President Abraham Lincoln. After the November election, he left for Georgia to rejoin his old regiment for Sherman’s “March to the Sea” but was instead given command of the 1st Brigade at Nashville and led them in a decisive battle against Confederate General Hood.

A few weeks later, he received orders to rejoin his old unit, the 70th Indiana, at Savannah, Georgia but after a brief furlough in Indianapolis, Harrison contracted scarlet fever which delayed him by one month. He then spent the next several months training replacement troops in South Carolina. After the South’s surrender, he reached his old regiment on the same day as the news of President Lincoln’s assassination.

General Harrison, with his 70th Indiana, participated in the Grand Review of Western Armies held on May 24, 1865 in Washington, D. C. and was mustered out of service with the regiment on June 8, 1865.

At the close of the war, Harrison at once entered upon his duties as reporter of the Supreme Court of the State of Indiana. In 1876, Harrison ran for governor of Indiana but was defeated in a campaign where the Democrats unfairly stigmatized him as “Kid Gloves.” He was elected to the United States Senate in 1881, and held that office for six years where he supported civil service reform, a protective tariff, a strong Navy, and regulation of the railroads. Senator Harrison was also a vocal critic of President Grover Cleveland’s vetoes of Civil War veterans’ pension bills. In 1888, Harrison was nominated by the Republicans for President of the United Sates partly because of his name, partly because of his war record and partly because of his popularity with veterans.

Benjamin came from a family with many years of public service to the country. His great grandfather, Benjamin Harrison V, was a signor of the Declaration of Independence and governor of Virginia. His grandfather, William Henry Harrison, was the first governor of the Indiana Territory, a congressman, a senator, and the ninth President of the United States. Benjamin’s father, John Scott Harrison, was a representative from Ohio.

During the presidential campaign of 1888, the Republicans made high tariffs one of the most important issues. In addition, a strong appeal for the veteran vote was made, based on Harrison’s war record and his votes, while in the United States Senate, in favor of pensions for veterans. Cleveland, on the other hand, had not fought in the Civil War and had consistently vetoed pension bills, claiming they would encourage massive fraud. Furthermore, he had offended many Union veterans by returning captured Confederate battle flags to the South.

Come On Boys!, Battle of Resaca, May 13th to 16th, 1864 This lithograph depicts Colonel Benjamin Harrison charging into the Battle of Resaca on horseback, leading the Seventieth Indiana Regiment. It was published by Kurz & Allison in 1888 during Harrison’s campaign for the presidency. (Image Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

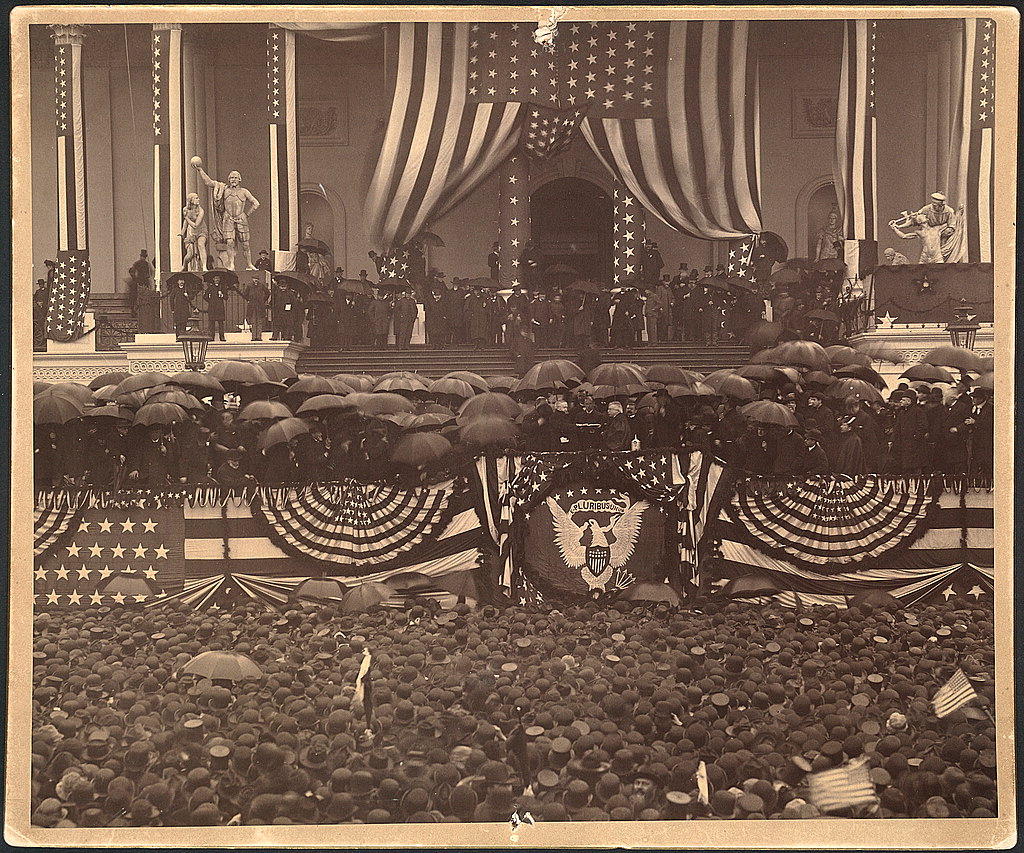

On election day, despite Cleveland garnering approximately 90,000 more popular votes, Harrison won sixty-five more electoral votes (233 to 168) and won the office of Twenty-third President, serving from 1889 to 1893. Harrison was also the Centennial President, elected one hundred years after George Washington, and was the central figure of the centennial celebration in New York. Benjamin Harrison was inaugurated on a cold, rainy day on March 4th, 1889 (Benjamin Harrison’s Inaugural Address).

Several significant pieces of legislation were enacted during his term in office. The Pension Appropriation Bill provided pensions for Civil War veterans and their families, and the Sherman Anti-Trust Act forbade business trusts and monopolies. The Land Revision Act permitted the president to create National Forest Reserves. He set aside thirteen million acres of forest land on public domain for the first time in the nation’s history, and established Sequoia, Yosemite, and General Grant national parks. On August 19, 1890, President Harrison signed into law “An Act to establish a National Military Park at the battlefield of Chickamauga,” the first federal legislation requiring the preservation of an American battlefield. Harrison did more than any other President, up to that time, to increase respect for the United States flag. By his order the flag waved above the White House and other government buildings. President Harrison also urged that the flag be flown over every school in the land. Harrison brought six states into the Union: North and South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, and Washington. He increased the role of the United States in global affairs, with the First International American Conference, attended by representatives from Latin American nations, to create new commercial and diplomatic ties. He strengthened naval power and increased the national armed forces. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 raised import duties to protect American made products. This was supported by the public at first, but ultimately became unpopular, when it resulted in inflationary domestic prices.

Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller administering the oath of office to Benjamin Harrison on the east portico of the U.S. Capitol, March 4, 1889.

(Image Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Caroline Harrison, the wife of President Harrison, was a gracious and friendly White House hostess, an effective contrast to her reserved husband. She was a supportive wife and a devoted caregiver to her family of 11 members, representing four generations, all living together at the White House. Mrs. Harrison, a talented artist, designed the Harrison White House china in 1891. She made many improvements to the Executive Mansion, by supervising a major renovation of the historic building, installing electricity, and restoring the conservatory. The Daughters of the American Revolution appointed her their first president-general.

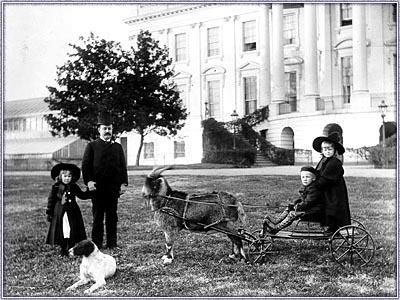

Although he was considered stiff and formal with acquaintances, President Harrison loved spending time with his family. His grandchildren were allowed to keep as many pets as they wanted on the grounds of the White House, including a goat named “His Whiskers” or “Old Whiskers.” The goat was used to pull the grandchildren around the grounds in a cart. One memorable story told of Harrison chasing the goat down Pennsylvania Avenue with his three grandchildren in tow and top hat in hand while waving his cane. For a while, the Harrison’s also owned two opossums named Mr. Reciprocity and Mr. Protection. President Harrison tried to escape Washington as often as possible, taking frequent secret hunting trips. On one of these trips he made national press when he mistakenly shot a farmer’s pig.

Photo taken on the White House lawn, in 1891, during President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. Pictured from left to right are Marthena Harrison, his son Russell, Benjamin Harrison “Baby” McKee, and Mary McKee. Also pictured are the family dog Dash and ‘Old Whiskers’ the pet goat.

(Image Source: Library of Congress, Title: “Baby McKee” in his goat cart)

Life in the White House was thoroughly photographed for the first time during Harrison’s term. In 1891, the Edison Company installed the first electric lights in the White House. Harrison, after being shocked by one of the electrical switches, mostly used the old gas lights. When he did use the electric lights, he often asked the White House staff to turn the switches on and off for him. The oldest known recording of any U.S. President is of Benjamin Harrison. It was recorded on an Edison wax cylinder sometime around 1889 (Vincent Voice Library – Hear President Harrison’s Voice). While the first decorated Christmas tree appeared in the White House in 1856 during the presidency of Franklin Pierce, the unbroken tradition of a White House Christmas tree did not begin in earnest until the Benjamin Harrison Presidency, in 1889. The 1889 White House Christmas tree was located in the Oval Room on the second floor (now known as the Blue Room) and was decorated with lit candles.

Portrait of President Benjamin Harrison by Alexander Lawrie

(Courtesy Indiana Soldiers’ Home)

White House Oil Portrait of Benjamin Harrison

By Eastman Johnson, 1895

(Source: White House Historical Association, White House Collection)

Caroline Harrison died in the White House on October, 25, 1892, after a long illness of tuberculosis. Following services at the White House and at the First Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis, she was buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

Two weeks after his wife’s death, Benjamin Harrison lost reelection to Grover Cleveland. The rigors of the office most certainly began to wear down the president. After being defeated by Grover Cleveland in his reelection bid, President Harrison, it is said, told his family that he felt as if he had been freed from prison. With his presidency behind him, he looked toward the future with renewed optimism.

Benjamin Harrison Home – Indianapolis, IN

Benjamin Harrison returned to his Delaware street home in Indianapolis and resumed his private law practice. He made changes to his home, including installing electricity and adding a large front porch. He remarried in 1896 to Mary Scott Lord Dimmick, who was the niece of his first wife, Caroline. He spent the years following his presidency as an “elder statesman.” delivering a series of lectures on constitutional law at Stanford University and serving with energy and dedication as chief counsel for Venezuela in its boundary dispute with British Guiana. He also authored a book, in 1897, on American government titled This Country of Ours.

Benjamin Harrison, who was the last Civil War general to serve as President, died from pneumonia on March 13, 1901, at his home in Indianapolis (read his obituary in the New York Times). On March 16, the National Guard formed a military procession to escort Harrison’s body from the Delaware Street home to lie in state at the Capitol Building. Survivors of Harrison’s Seventieth Volunteer Regiment led as the honor guard. Businesses were closed, flags were at half-mast, and black crepe was hung on buildings and lamp posts. On March 17, President William McKinley led the funeral procession from Harrison’s home to the First Presbyterian Church. The streets on the route were lined with quiet, respectful on-lookers, dressed in black. Space in the church was limited, and admittance cards were given to those who attended the funeral service. Harrison was buried next to his first wife, Caroline, at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana (Section 13, Lot 57). The poet James Whitcomb Riley described Harrison, in his funeral eulogy, as a man both fearless and just. General Lew Wallace, nearly a lifetime friend of ex-President Harrison, said of him after learning of his death: “Ten days ago Benjamin Harrison was the foremost man in America. I make no exception. He had every quality of greatness — a courage that was dauntless, foresight almost to prophecy, a mind clear, strong, and of breadth by nature, strengthened by exercise and constant dealing with subjects of National import, subjects of world-wide interest. And of these qualities the people knew, and they drew them to him as listeners and believers, and in the faith they brought him there was no mixture of doubt or fear. The sorrow for him must be universal.” Benjamin left the bulk of his estate, valued at about $400,000, to his second wife, and their four-year-old daughter, Elizabeth.

President Harrison’s Grave Stone Inscription

BENJAMIN HARRISON.

August 20, 1833.

March 13, 1901.

LAWYER AND PUBLICIST.

COL. 70th REG. IND. VOL. WAR 1861-1865.

BREVETTED BRIGADIER GENERAL, 1865.

U. S. SENATOR, 1881-1887.

PRESIDENT, 1889-1893.

STATESMAN, YET FRIEND TO TRUTH,

OF SOUL SINCERE;

IN ACTION FAITHFUL, AND IN

HONOUR CLEAR.

Grave of President Benjamin Harrison as it appeared in 1904.

(Image Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection)

Grave of President Benjamin Harrison as it appears today. (Photo courtesy of Brandon R. Smith)

An outpouring of tributes to Harrison was published in newspapers across the nation. As president, he was remembered for his conscientious devotion to duty with absolute integrity and service in the best interests of the country. He was lauded as a great statesman, lawyer, and orator. During his presidential years, perhaps due to shyness, he was at times criticized for being aloof, cold, and unsympathetic under the stress of public duty. But those who knew him personally, saw him in an opposite light: unpretentious, genial, generous, and tender hearted. Years later, the American intellectual Henry Adams spoke of Harrison as the best President since Lincoln.

Sources:

Miller Center for Public Affairs – American President Benjamin Harrison

President Benjamin Harrison Home Official site

The White House – Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison A Resource Guide – Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress

The White House Historical Association – Classroom Picturing the President’s House

**********************

“I have never been able to think that this day is one for mourning, but think that instead of the flag being at half mast it should be at the peak. I feel that the comrades whose graves we honor today would rejoice if they could see where their valor has placed us. I feel that the glory of their dying and the glory of their achievement covers all grief and has put them on an imperishable roll of honor.”

Decoration Day, May 30th, 1891